Furniture made from lobster traps and informed by metal music feature in the independent furniture design studios in , Canada, presented as part of our series.

Just north of the border with the United States, Montreal is the largest city in the Canadian province of Quebec and the second largest Francophone city in the world, after Paris.

Once a major hub of the fur trade in North America, Montreal had a thriving industrial economy in the 20th century. It is well known from a design perspective for its 1967 International and Universal Exposition (Expo 67), where local architect presented the futuristic apartment complex.

The city has been dealing with a process of de-industrialisation for decades and relatively cheap rent, skilled labour and large post-industrial spaces have enabled a thriving arts scene.

Like , it received a UNESCO City of Design designation. The citation for the states that the city has a design industry that accounts for 34 per cent of the total economic input of its “cultural sector” and that as many as 25,000 professional designers are working in the city.

It has also become a hub of the study and research of artificial intelligence, with Google and Microsoft both opening research centres in the city.

Innovative uses of industrial materials

“Named a UNESCO City of Design, Montreal’s design industries and creative fields are currently thriving, driven by a unique blend of historical, social, and economic factors,” Martin Racine, graduate program director at ‘s Department of Design and Computation Arts, told Dezeen.

Racine cited both lighting design and circular design as strengths of the city’s scene.

Montreal does have a number of developed, internationally recognized houses putting out high-quality designs, such as lighting studio , which has provided starts to many young designers in the city.

Racine also noted that many designers are using industrial materials, but are “stripping them of their cold, industrial image through innovative texturing, hammering, polishing, and lacquering techniques”.

“This creative reimagining allows these materials to permeate various parts of the home, from the kitchen to the living room, showcasing Montreal’s bold and imaginative design ethos,” he continued.

Read on for nine independent furniture designers at different points in their careers, working in a variety of styles in Montreal.

Studio Clara Jorisch

‘s solo practice explores the translation of organic forms into sculptural furniture pieces. Working mostly in glass, she told Dezeen that she is currently moving away from industrial glass and towards recycled forms including developing a process of fusing plate glass with pate de verre.

She recently moved into modular furniture design and believes that young people should be reconsidering the place of design in society.

“I think the place of design in the world is changing. The current issues and needs are no longer the same as at the start of industrialization and there is perhaps a philosophical reversal taking place,” she said.

“Probably like many young people my age, I think that my approach to design is one of degrowth and inclusion. I also believe in the revival of vernacular craft techniques and the culture of knowledge transmission it implies.”

Cyrc

co-founders Daniel Martinez and Guy Snover use recycled plastics and 3D printing to create sculptural decor pieces – including bowls and vases – for the home.

Snover utilises his industrial design background to work directly on developing and fixing 3D printers used for the brand, with the business model of the young studio based on circular design.

“We’re using plastic because it allows us to create a fully circular business model and manufacture in-house,” Martinez and Snover told Dezeen.

“Recycling is a failed program at the municipal level, but it can be done if you design for it and do it yourself. We want people to have the experience of returning something they own to the producer at the end of its life, knowing it will be made into a new object.”

Simon Johns

, who creates furniture in a variety of materials including wood, clay, gypsum cement, and glass, tries to make materials “resemble things that they weren’t intended to”.

“I hope my work asks more questions than it provides answers to,” he told Dezeen.

“I like when form and texture in a material evoke a different material, and the experience initiates an emotional response somehow similar to what we can experience in the presence of nature. If that can happen, then we aren’t thinking about woodworking, or ceramics, or plaster, or craft, or even function.”

After graduating from Concordia University, where he worked on set design, Johns took a trip to New York in 2015, where he decided to launch a career in furniture design.

Thom Fougere

Trained as an architect, later focused on furniture and became the creative director of Canadian furniture giant at only 23. He worked there for 10 years before setting off on his own in 2019.

Fougere’s practice revolves around a fascination with wood and woodworking techniques and has drawn influence from traditional communities such as the Shakers. He told Dezeen that his designs usually respond to the immediate needs of a commission.

“Some may be as simple and nuanced as enhancing one’s connection to nature, while others are more pragmatic and complex, such as developing tools for fostering a healthy work environment,” he said.

“My general approach is to uncover an intuitive or poetic solution to these problems, which often comes as a result of material exploration and research, observation, drawing, and make those discoveries as simple and legible as possible. The hope is to make the end result feel inevitable, beautiful and practical all at once.”

Éditions 8888

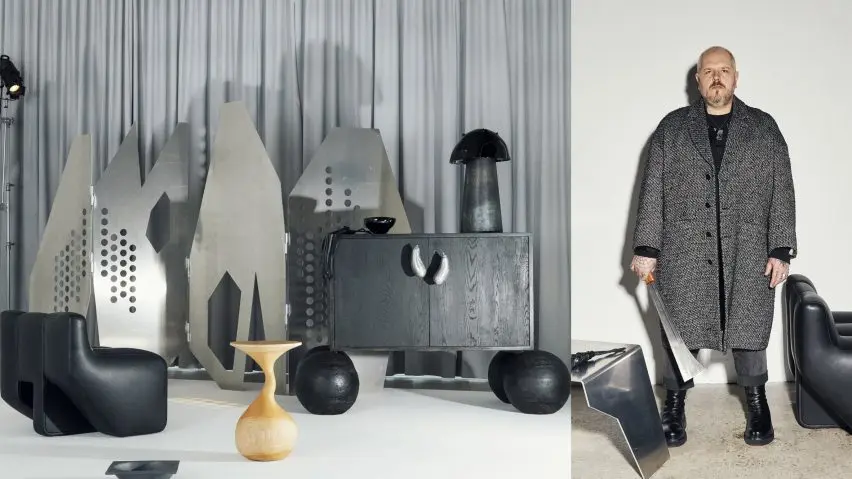

is the brainchild of Jean-Michel Gadoua, who aims to bring a heavy metal edge to furniture design, working in steel, aluminium, black leather and concrete.

Trained as a graphic designer, Gadoua uses the studio as a creative outlet and also as a protest against what he views as “industrial and impersonal manufacturing”. His designs, which he refers to as Brutaluxe, take humorous and often dark names, such as the Nuclear Assault Cabinet and

the 1,000,000 Dead Hippies Lamp.

The designer who uses local materials and often puts on exhibitions is not trying to solve any specific problems with his designs.

“While all my work is fully functional, it is created first and foremost as an aesthetic object,” he told Dezeen.

Lauren Goodman

utilises waste to create sculptural furniture, with her most recent projects using discarded lobster traps to make shelving and seats.

Trained at the University of Toronto and RISD, Goodman began as a woodworker, and then, compelled by the multitude of waste, transitioned into sculptural furniture after graduate school. She said that the waste streams she works with inform the character of her work.

“The chance to transform this otherwise unwelcome material into a functional piece of furniture is really invigorating to me so I keep pursuing paths like this,” she told Dezeen. “Adopting a model that prioritizes the use of materials that already exist, over something clean and new, can begin to respond to our ongoing problems with waste,”

“I believe that micro changes carried out collectively over time can lead to revolution and I want to be part of the design community who are working towards that radical transformation.”

Reggy St-Surin

recently started as an industrial designer, after transitioning from architecture, and created an upholstered chair that can stand in many different positions, like a jack. He recently joined an industrial fabrication shop, where he is working as a welder.

St-Surin said that he aims to bring an element of play to designs and described the work he is creating as “soft sculptures”.

“I want to encourage people to get a little funky and try to bring something new to the table,” he told Dezeen.

“Also, it might not be through my work, but it is nice to represent the black community in this scene, as it can feel a little deserting.”

Studio Botté

Founded by Philippe Charlebois-Gomez, creates lights from upcycled materials sourced through urban mining, city scavenging and donations from a community he has built around his brand – and this sourcing method often dictates the forms of the objects he creates.

Having once worked for Lambert & Fils, Charlebois-Gomez brings his expertise in lighting design to the project of upcycling and often provides an outlet for products that may be discarded.

“[It means] one less item brought from overseas and demanding new materials to be extracted,” he told Dezeen.

“We bring the new and take your old! Then we use the old to make some new! The way design has been is most likely going to fall and upcycling will come to save the day!”

Will Choui

creates brutalist furniture, often using metal rendered in bright colours and featuring repeating patterns. His designs usually take direct reference from a specific building such as the .

A graduate of RISD, Choui often collaborates with others in the scene such as Simon Johns and lighting company . He told Dezeen that durability is a high priority when creating his collections.

“I’ve been primarily working with aluminum. I appreciate its lightweight yet sturdy nature, and its aesthetic appeal both in raw and finished forms,” he said.

“My goal is to create furniture that lasts a lifetime, emphasizing good design and sturdy construction to prevent it from becoming disposable waste.”

North American Design 2024

This article is part of Dezeen’s series selecting independent furniture and product design studios from cities across Canada, Mexico and the United States.

The first edition of this series is created in partnership with Universal Design Studio and Map Project Office, award-winning design studios based in London and now in New York. Their expansion into the US is part of The New Standard, a collective formed with Made Thought.